A new study suggests a way to diagnose this disease early, when interventions may be most effective.

The very early stages of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) can be difficult to detect. Changes in the brain can begin a decade or more before any memory or thinking problems occur. When the first symptoms do appear, they can seem like normal forgetfulness.

Recent research on the gut microbiome suggests a new way to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease early on, when treatment can be most effective.

The study, published June 14 in Science Translational Medicine, found that people in the earliest phase of the illness, who have no outward signs of decline, have a different composition of microbes in their intestines than healthy people.

“Previous studies have shown that the gut microbiomes of persons with clinical Alzheimer’s disease [when impairment of memory and cognition is apparent] are different from those of persons who are cognitively healthy,” says the lead study author Aurora Ferreiro, PhD, a postdoctoral research associate at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “We asked how early in the progression of AD can those gut microbiome differences be detected — and the answer is quite early. The potential utility of the microbiome in early screening for preclinical AD and AD risk is supported by these results.”

Further Evidence of the Gut-Brain Connection

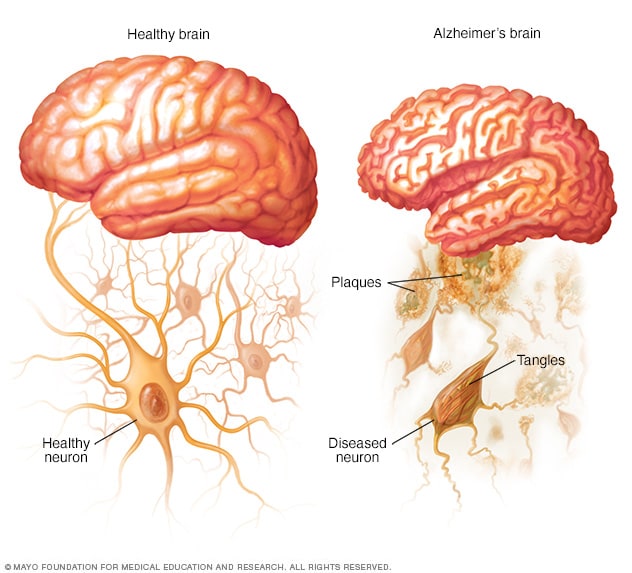

For this analysis, 164 cognitively normal participants ranging in age from 68 to 94 were screened via PET and MRI brain scans and cerebrospinal fluid analysis. The researchers were looking for clumps of the proteins amyloid beta and tau, which are considered to be the distinguishing characteristics of Alzheimer’s even at preclinical stages.

Nearly a third (49) had these indications of early Alzheimer’s.

Looking at stool samples, investigators discovered that even though all the subjects were following basically the same diet (according to their responses to food questionnaires), those with amyloid beta and tau accumulations had markedly different gut bacteria from their “healthy” counterparts. Dr. Ferreiro notes that her team identified seven species of bacteria that “significantly improved our ability to predict whether an individual had preclinical AD or not.”

She stresses that the research team is not claiming that specific bacteria increase Alzheimer’s risk. The findings only point to a connection between gut microbiome composition and AD.

Gut Microbiome Tests Could Potentially Help Alzheimer’s Diagnosis

If the results are validated by further study, Ferreiro sees a potential for the use of gut microbiome tests to determine a person’s risk of developing dementia.

“A person flagged [for AD] based on gut test results might be referred to follow-up screening for established AD biomarkers [such as tau and amyloid beta clumps],” she says.

Christopher Damman, MD, a clinical associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, calls the possibility of improving Alzheimer’s diagnosis through gut data “exciting.”

“Tests using CSF [cerebrospinal fluid] and imaging are good, but if you can make them better, then you’ll be able to more accurately identify people who are likely to go on to develop Alzheimer’s,” says Dr. Damman, who was not involved in the study. “So this is a step in the right direction.”

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, early diagnosis provides a better chance a patient will benefit from various treatments, including medications and lifestyle changes, such as controlling blood pressure, stopping smoking, exercising more, and staying mentally and socially active.

“Once AD is symptomatic, there is usually neurodegeneration involved, and it’s difficult to come back from that,” says Ferreiro.

A coauthor of the study, Beau Ances, MD, PhD, a professor of neurology at Washington University School of Medicine, foresees a time when people may be able to provide a stool sample and find out if they are at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

“It would be much easier and less invasive and more accessible for a large proportion of the population, especially underrepresented groups, compared with brain scans or spinal taps,” said Dr. Ances in a press release.

Can Changing the Gut Lower Alzheimer’s Risk?

At this point, it’s impossible to say if microbial changes in the gut are a result of Alzheimer’s disease or if these changes could be influencing the disease itself.

Because participants in this investigation were basically eating the same diet, no conclusions could be made as to whether diet might impact dementia risk.

So far, there is no evidence that eating or avoiding a specific food can prevent Alzheimer’s disease or age-related cognitive decline, according to the National Institute on Aging. But the organization does mention that what we eat could affect the aging brain’s ability to think and remember. The Alzheimer’s Society indicates that a diet rich in fruit, vegetables, and cereals, and low in red meat and sugar helps reduce dementia risks.

“One could speculate that if you can identify a diet that moves these microbiome markers in a positive way, that could then be beneficial, but that’s way beyond what the study tells us,” says Damman.

As far as future research is concerned, the study authors have launched a five-year follow-up investigation designed to figure out whether the differences in the gut microbiome are a cause or a result of the brain changes seen in early Alzheimer’s disease.